La lectura “es

muy importantísima”

Esta opinión sobre la lectura fue escrita por una

joven de 14 años que participó en nuestra encuesta sobre la lectura. En el

cuestionario, se les pidió que escribieran su opinión sobre la lectura. La idea

de que la lectura es “importante” se refleja en la mayoría de las opiniones

proporcionadas por los 250 encuestados, alumnos de 2º y 3º de secundaria en dos

escuelas de gobierno. Entonces, según ellos, ¿para qué es “muy importantísima”

la lectura? Todavía no tenemos las estadísticas exactas, pero resulta obvio que

para la mayoría, la lectura es importante como herramienta para “leer mejor”,

“aprender”, “obtener conocimientos/información”, “desarrollar la comprensión”,

“escribir correctamente”, “ayudar en la

ortografía” o “con beneficios cultos”. Fueron muy pocos los que mencionaron que es

“divertida” o cuyas respuestas reflejaran gusto o placer. Otras respuestas

simplemente indicaron que es “aburrida”, “no es para mí” y/o que no tienen

tiempo para dedicarle a los libros.

Las opiniones sobre la lectura son casi idénticas a

las que expresaron los 90 jóvenes que participaron en el estudio original y

respondieron a la misma indicación cuando se aplicó el cuestionario en 1992.

Esto fue lo que yo escribí en el análisis de estas opiniones en mi tesis:

A pesar de que estas opiniones son breves, las

contradicciones y la repetición de ciertas palabras e ideas son significativas,

tales como las palabras “útil” y “conocimiento”. Los adjetivos utilizados más

frecuentemente fueron “aburrido”, “interesante” y “bonito”; los verbos fueron

“sirve”, “enseña” y “aprende” y el

objetivo de estas acciones era obtener “cultura”, “conocimientos”,

“vocabulario” y “ortografía”. Las

opiniones parecen reflejar la idea que la lectura es un medio para lograr un

objetivo y no como un fin en sí misma, en términos de Rosenblatt,* se refieren

a una lectura “eferente”. Estos comentarios mostraron que los adolescentes

reconocieron la “utilidad” de la lectura y los libros eran relacionados con actividades

escolares y el aburrimiento. Parece haber una identificación casi total de la

lectura como una actividad curricular, una obligación, pero no como una

actividad que puede ser divertida y entretenida.

Casi 25 años más tarde, se repite este escenario aunque

parece que la cuestión de “tener tiempo” para la lectura se ha vuelto más

problemática: en ese entonces la lectura competía sobre todo con la televisión;

ahora compite también con la computadora, las redes sociales digitales, el

teléfono celular, las películas y/o videos, el i-pod y los videojuegos, entre

otros. En lo que parece una actitud contradictoria, muchos jóvenes apuntaron

que recurren a la lectura cuando están “aburridos” y no hay nada más que hacer.

Estos no son resultados sorprendentes, lo que sorprende

es que existen algunos lectores jóvenes que se toman el tiempo para leer un

libro y tienen una opinión favorable de esta actividad, no por su “utilidad”,

sino por el placer que les proporciona. El placer se manifiesta sobre todo en

la palabra “divertido” y en la idea de que estimula la imaginación. En la reciente

encuesta, las respuestas que nos ayudan a entender lo que quieren decir con

esto son las que describen por qué les gustó un libro en particular, es decir,

las respuestas que no se refieren a la “importancia” de la lectura sino a la

lectura “significativa”. Las respuestas más elaboradas tienen que ver con

libros particulares que adquirieron un significado personal, ya sea sobre sus

relaciones con otros, la búsqueda de su identidad, sus cuestionamientos acerca

de la vida (o la muerte), entre otras cosas que preocupan a un adolescente del

siglo 21, pero que también preocuparon a los jóvenes hace casi un cuarto de siglo. La lectura significativa les

provocó curiosidad, los “llevó al mundo

de la fantasía”, involucró sus sentimientos y las emociones, tuvo que ver con la

“identificación” con los personajes o con la distracción de sus propios problemas.

De nuevo, las respuestas son casi idénticas a las mencionadas en la encuesta

original.

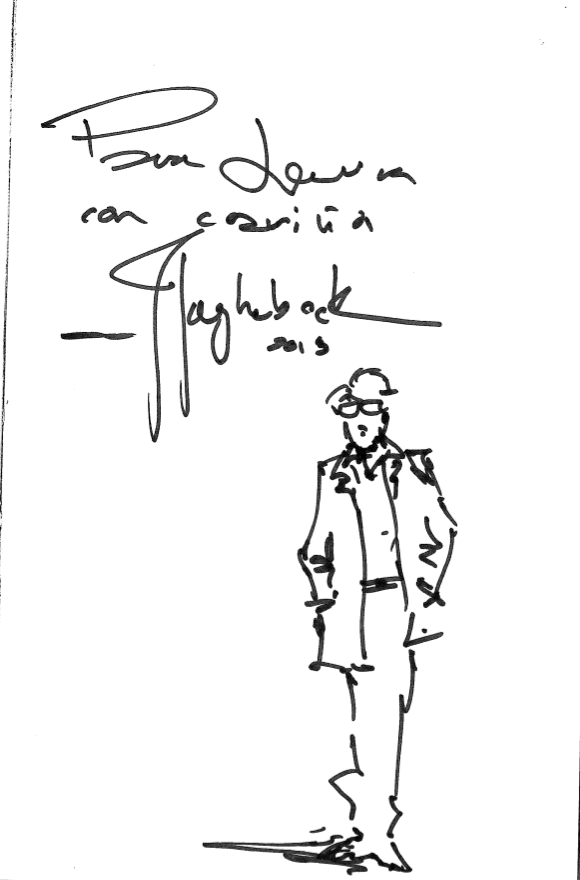

En el estudio original se

trabajó con jóvenes que se describieron como “poco lectores”. Leímos y discutimos tres libros juveniles,

seleccionados con la idea de que trataban de temas que les podían interesar,

con personajes jóvenes y con lenguaje accesible: El mundo de Ben Lighthart

de Jaap ter Haar (1983, Ediciones SM); No pidas sardinas fuera de temporada

de Andreu Martin y Jaume Ribera (1988, Alfaguara) y El ladrón de Jan

Needle (1993, Fondo de Cultura Económica). Casi todos los participantes

expresaron su gusto por estas lecturas ya que se habían entretenido y

divertido, sobre todo porque pudieron relacionarse o involucrarse de alguna

manera con los personajes. En la conclusión a la tesis, esto fue lo que

escribí:

El resultado más satisfactorio

de la investigación fue que algunos alumnos manifestaron un placer en haber

terminado y disfrutado un libro y el deseo de continuar leyendo.

En los siguientes blogs hablaremos no sólo sobre los

resultados más específicos de la encuesta, sino también sobre los tres libros

que escogimos para la investigación actual. A diferencia del primero estudio,

sólo uno de los tres es una novela, los otros dos son textos con imágenes: una

novel gráfica y un libro álbum. Por lo pronto, parece que la novela gráfica ha

sido un éxito, varios de los lectores lo han calificado como “chido”. Como dijo

Juan Domingo Argüelles, editor y autor de varios ensayos sobre la lectura, en

una de las mesas magistrales durante el Congreso de IBBY en México, “si un

chico dice que un libro es ‘chido’, ya la hiciste.”

La pregunta es, entonces, ¿puede un libro ser “muy

importantísimo” y “chido” a la vez?

*Rosenblatt, L.M. (1978). The Reader, the

Text and the Poem: The Transactional Theory of the Literary Work,

Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Reading is “very much important”

This opinion

about reading was written by a young girl of 14 who participated in our reading

survey. In the questionnaire, we asked them to write their opinion about

reading. The idea that reading is “important” is reflected in the majority of

the opinions given by the 250 respondents, students in second and third year

from two government secondary schools.

So, according to

them, why is reading “very much” important? We still do not have the exact

statistics, but it is obvious that for the majority, reading is important

mainly as a tool to “read better”, “learn”, “obtain knowledge/information”,

“develop comprehension”, “write correctly”, “help with spelling” or “with

cultural benefits”. There were only a few mentioned that it was “fun” or whose

answers reflected a sense of enjoyment or pleasure. Other replies simply

indicated that it was “boring”, “not for me” and/or that they did not “have

time” to spend with books.

These opinions

about reading are almost identical to those expressed by the 90 young people

who participated in the original study and replied to the same request when the

questionnaire was applied in 1992. This is what I wrote in the thesis when I

analysed these opinions:

Although these opinions are brief, the contradictions and the repetition

of certain words and ideas are significant, like the words "useful"

and "knowledge". The adjectives used most frequently were "boring",

"interesting" and "nice"; the verbs were "serve",

"teach" and "learn" and the object of these actions were

"culture", "knowledge", "vocabulary" and

"spelling". These opinions seem to reflect the idea that reading is a

means to achieve an objective and not an end in itself, in Rosenblatt's terms,

they are talking about "efferent" reading.* These comments show that

adolescents recognized reading as "useful" and equated books with

school activities and boredom. There seems to be an almost total identification

of reading as a curricular activity, as an obligation, but not as an activity

that can be fun and entertaining.

Almost

25 years later, this scenario is repeated, although it seems that the issue of

“having time” to read has become more problematic: at that point in time,

reading competed mainly with television; now it also competes with the

computer, digital social networks, cell phones, films and/or videos, i-pods and

other music gadgets and videogames, among others. In what appears to be a

contradiction, many young people wrote that they read when they were “bored”

and had nothing else to do.

These

results are not particularly surprising, what is surprising is that there are

some young readers who take the time to read a book and have a favorable

opinion of this activity, not because it is “useful”, but because of the

enjoyment they derive from it. This pleasure is manifested mainly in the word

“fun” and the idea that it stimulates the imagination. In the more recent

survey, the responses that help us understand what they mean by this are the

ones in which they describe why they liked a certain book, in other words, the

responses that don’t refer to the “importance” of reading but to a

“significant” text. These usually more elaborate replies were about particular

books that had a personal significance, whether this was about relationships

with others, their own search for identity, questions about life (or death),

among the other things that preoccupy an adolescent in the 21st century, but

that also preoccupied young people nearly a quarter of a century ago.

Significant texts provoked their curiosity, took them “to the world of

fantasy”; involved their emotions and feelings; and had to do with

“identifying” with the characters or distracting them from their problems. Once

again, the replies are almost identical to those mentioned in the original

survey.

In the

original study, I worked with young people who described themselves as reading

only “a little”. We read and discussed three YA books, selected with the idea

that they were about themes that could interest them, with characters their age

and accessible language. These were the Spanish translations of The World of

Ben Lighthart by Jaap ter Haar (1983, Ediciones SM); Don’t Ask for

Sardines out of Season by Andreu

Martin y Jaume Ribera (1988, Alfaguara) and The Thief by

Jan Needle (1993, Fondo de Cultura Económica). Almost all the participants

expressed their liking for these books. They found them “fun” and

“entertaining” mostly because they had been able to relate to or become

involved with the characters in some way. This is what I wrote in the

conclusion of the thesis:

The most satisfying result of

the research was that a few students manifested a pleasure in having finished

and enjoyed a book and a desire to continue reading.

In the next

blogs we will write not only about the more specific results of the survey but

also about the three books that we chose for our current research. One of the

differences between the projects is that in the first one all three were novels

but in the current one, two of the texts have images, one is a graphic novel

and one is a picturebook. We have started reading the graphic novel and so far

it has been a success. Several readers have described it as “cool”. As Juan

Domingo Argüelles, editor and also

author of many essays on reading, said

at one of the panel discussions during the IBBY Congress in Mexico, “if a kid

says that a book is ‘cool’, you’ve done it”.

The question is,

then, can a book be “very much important” and “cool” at the same time?

*Rosenblatt, L.M. (1978). The Reader, the

Text and the Poem: The Transactional Theory of the Literary Work,

Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press.